There’s a common malfunction that occurs when well-intentioned people open their mouths to say no: The word “yes” tumbles out instead.

We’ve all been there, says Vanessa Bohns, department chair and professor of organizational behavior at Cornell University. No is a deceptively short, simple word that can trigger several layers of anxiety for the person trying to say it. For starters: What does it reveal about our character? “We worry that we’re essentially communicating that we’re not a helpful person; we’re not a nice, kind person; we’re not a team player,” Bohns says. “We’re too lazy to take something on, or we don’t want to work hard.”

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]At the same time, she adds, we’re likely stressing over how that “no” might offend the other person, and what it conveys about our relationship with them. As Bohns puts it, you might think “it’s telling the person, ‘Your standing with me is not what you thought it was. We’re not actually that close.’” In reality, however, such concerns are often overblown.

In fact, there’s an array of benefits associated with learning to say no. “If you’re saying yes to everything, people are more likely to ask you again and again,” says Bohns, who’s the author of You Have More Influence Than You Think. “You wind up being the person who gets all the asks, and that can lead to burnout, problems with work-life balance, feeling like you’re being taken advantage of, and a loss of autonomy.” Plus, an inability to say no could cause priorities such as hobbies, relationships, or projects to suffer. “Each time we say yes to something, we’re implicitly saying no to something else,” Bohns points out.

Saying no with conviction begins with having a clear sense of what is and isn’t worth your time. That can become fuzzy, especially given social pressure and the weight of obligation. Gain clarity by utilizing a simple cost-benefit framework, suggests Vanessa Patrick, associate dean for research at the Bauer College of Business at the University of Houston, and author of The Power of Saying No. Essentially, you’ll weigh the costs of saying yes for you against the benefits for the other person, and then make a judgment.

Some requests, for example, will be easy for you to do and confer great benefit to the asker. Writing letters of recommendation falls into this category for Patrick. “As a professor, it’s relatively easy to do—but the benefit to my students is huge. They could get into the college of their dreams,” she says. Others will require a lot of work on your end, and not mean a great deal to the people on the other side. “I call these ‘bake your famous lasagna’ asks,” she says. Imagine you’re invited to a dinner party, and someone asks you to make a fancy dish that calls for hours of preparation. “Yes, it might be delicious, and it might be something you’re famous for, but it’s going to be on the table with everybody else’s store-bought cookies,” she says. It’s not worth the time—so say no with oomph.

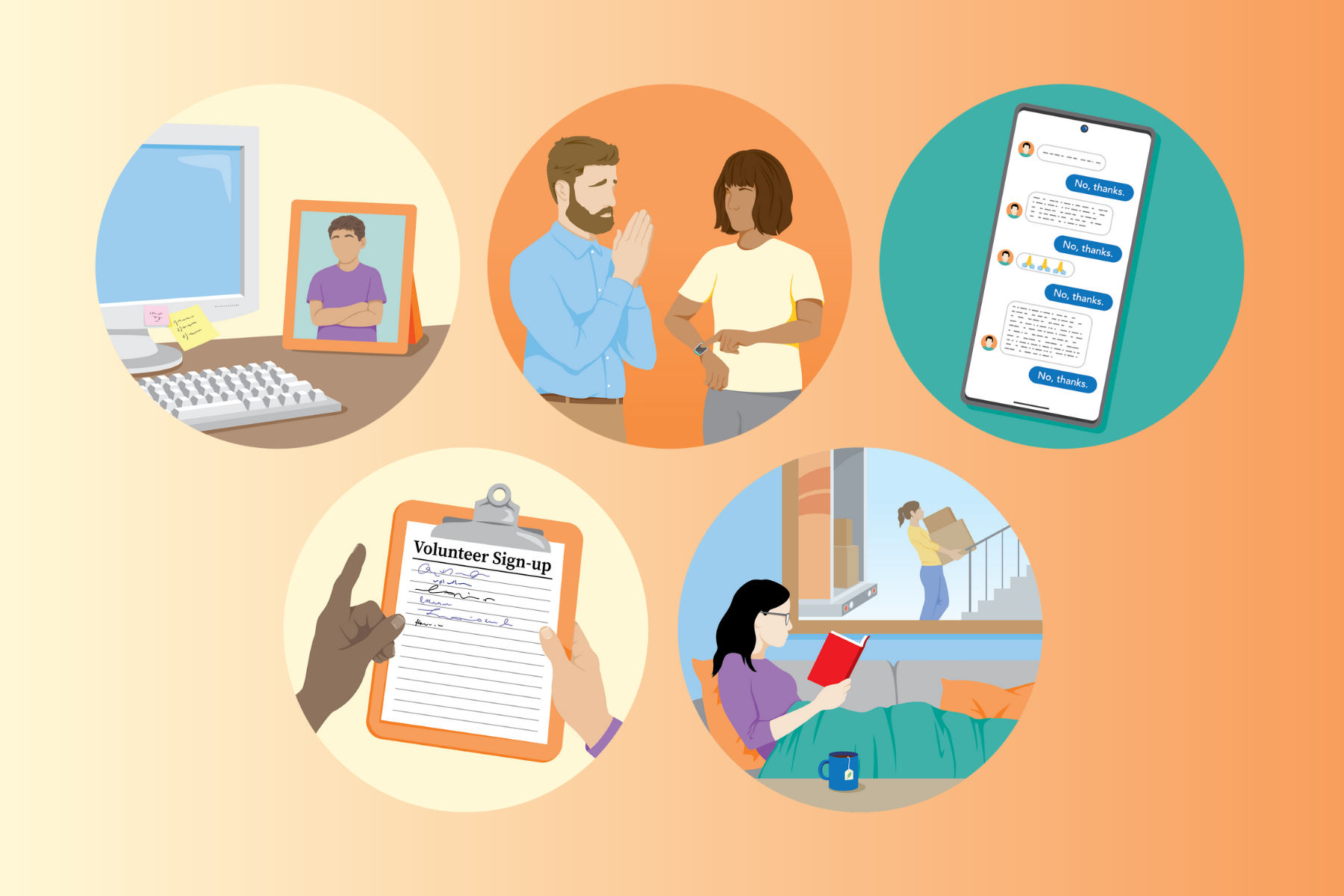

If that still makes you shudder with dread, remember that practice helps. Experts say these strategies can help you get better at saying no.

Be intentional about what you communicate.

You might have heard the tip that “no” is a complete sentence. Sure—but as Bohns points out, leaving it at that is often pretty uncomfortable. Instead, she advises communicating three things: “It’s not because of me, it’s not because of you, and it’s not because of us.”

One way to do that is by thanking people for thinking of you—which reassures them that they didn’t do anything wrong by asking. Then, follow-up with a short explanation: “I wish I could, but I just don’t have the time right now.” That helps make it clear that your “no” isn’t a poor reflection of your own character (you would do it); it’s not the other person (you appreciate the ask); and it’s not an indictment of the relationship (it’s simply circumstantial), Bohns says.

Have a planned phrase for more casual encounters.

Not every situation, of course, calls for such a thoughtful approach. Think through times when you’ve gotten stressed over delivering a quick “no,” and then brainstorm phrases you could use in the future. Bohns, for example, is often asked to donate to some cause or another as she checks out at the grocery store. She now has a go-to response: “I already donated this year.” “It’s true, and it’s a way of saying, essentially, that I’m still a good person,” she says. Having a planned phrase in mind makes these potentially awkward scenarios much more comfortable.

Read more: 6 Ways to Set Boundaries at Work—Even When It’s Uncomfortable

Buy time.

If you tend to accidentally say yes whenever you’re put on the spot, find ways to buy time. You might say, for example: “Let me think about it and I’ll get back to you,” Bohns suggests. Or: “Let me check and I’ll respond by email.” That way, you can spend time privately processing the request, making a mindful decision, and if necessary, declining in whatever format is most palatable, whether that’s electronically or in person.

Be matter of fact.

Delivery is everything when you’re saying no. Aim to be matter of fact, advises Ellen Hendriksen, a clinical psychologist and author of How to Be Yourself. That means not over-apologizing or otherwise acting as though you’re doing something wrong. “If we signal that this is no big deal, and we’d like to help but can’t, that sets the tone for a more neutral interaction,” she says. One way to do that: “I counsel students to ask difficult questions in the same tone of voice they would use to order a sandwich,” she says. That strategy can be applied to saying no, too. You can’t help your sister-in-law’s second cousin move into her new apartment? Treat it like you’re ordering a tuna sub, hold the mayo.

Adopt the broken-record technique.

There’s always that one guy who won’t take no for an answer. If someone is applying undue pressure, utilize what Hendriksen describes as the broken-record technique. “It’s sticking to your answer—giving the same answer again and again,” she says. “You don’t have to be soulless about it; you can empathize and be polite. But it’s important not to let your no evolve into a ‘maybe’ or an ‘OK, just this once.’” Occasionally, the asker will get irritated, she adds—but usually after two or three times repeating yourself, even the most persistent people will get the message.

Read more: 8 Rules for Navigating Your Family Text Chain

Reinforce your message with body language.

It’s important to align your body language with what you’re saying verbally. That could mean smiling, leaning forward, or parting with a hug to make it clear that your no is about you and not a rejection of the other person, Patrick says. “It will help you come across much more persuasively in your refusal,” she says. Meanwhile, aim to avoid body language that indicates you’re nervous or vulnerable; for example, by averting eye contact.

Carry a visual reminder of why your “no” matters.

If you say yes to that committee at work, or to bringing two dozen cupcakes to book club, what will you miss out on? Bohns suggests carrying an inspirational photo that serves as a reminder. “It could be your dog; it could be your kid,” she says. “It could be some hobby that you love.” Put it near your computer or phone, and when you really don’t want to do something—but feel obligated to say yes—it will give you strength. Pick it up and remember: “If I say yes to this, I’m basically saying no to when my daughter asks me if we have some free time to read a book later.”

Ask people questions in a way that allows them to say no.

As you fine-tune your “no” skills, consider making it easier for other people to decline your requests, too. It benefits both parties, Bohns points out: Most of us would prefer to receive one final no than to have someone say yes—only to bail at the last minute. Because it’s difficult for people to say no when they’re put on the spot, especially in face-to-face situations, word your request in a way that allows them time to think about it. When discussing a project with her grad students, for example, she often says: “I think you might like this project, but I don’t want you to feel pressure. Sleep on it, and then shoot me an email.”

Bohns’ unpublished research suggests that when making a request, we often say, “You can totally say no.” But the people we’re talking to know that—the problem is they can’t figure out how to say it. One solution, then, is to give them the words to do so. For example, you might put it like this: “If you don’t want to do it, just say you can’t right now.” “Basically give them a phrase that’s acceptable to say back to you,” Bohns says. “Like, ‘Here’s some words I will accept as a no.’ We’ve found that makes people more comfortable.”

Post A Comment:

0 comments: